NIH planned to keep testing on beagles through 2026 before halting experiments

BETHESDA, Md. (7News) — Earlier this month, the U.S. Navy shut down all experiments on cats and dogs.

Days before the National Institute of Health (NIH) shut down its last beagle experiment.

That specific research killed five dogs. It all comes after years of public and congressional pressure to find alternatives to animal experiments.

7News has discovered the NIH was recently planning on continuing those experiments through 2026, which would have meant another 19 beagles dead.

I-Team Investigative Reporter Scott Taylor has been following the push for alternative animal testing for an extraordinarily long time.

Internal documents from the National Institutes of Health show U.S. taxpayers paid more than $15,000 in 2024 for five beagles who were experimented on to learn more about septic shock at a research facility in Bethesda, Maryland.

All five 14-month-old beagles died.

That experiment shut down in early May, but 7News is learning much more about how many beagles were on schedule to be killed and how those animals were treated.

All in the name of science.

SEE ALSO | New research: Dog and cat experiments could end in federal labs by 2036

White Coat Waste Project, a DC-based taxpayers' watchdog group, obtained the exclusive records through a Freedom of Information Act request and shared them with the I-Team.

As recently as April 15th, NIH told Congressional leaders the beagle research was ongoing, and NIH called the experiments painful.

Multiple vein catheters were implanted, and throats were cut to embed trach tubes.

NIH has been doing experiments like these on beagles for decades.

It says current canine models offer the ability to induce septic shock that mimics what occurs in humans.

Earlier this month, after nine years of pressure from the public, the White Coat Waste Project, and lawmakers, the federal government confirmed with 7News that the beagle experiments are now shut down.

Documents show NIH planned on using more of your tax dollars to fund the experiment through August 2026. If allowed to continue, it would have cost the lives of 24 beagles.

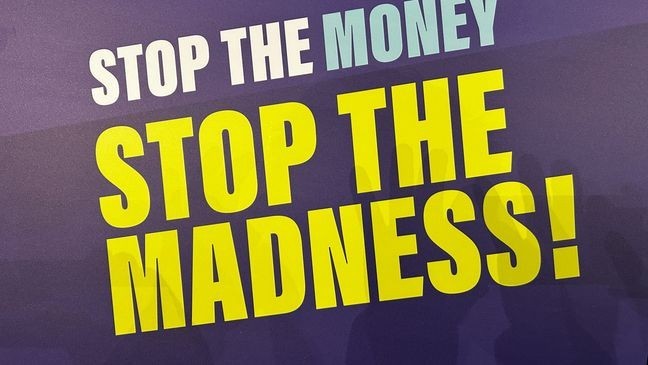

The White Coat Waste Project believes the amount of tax dollars burned by NIH and the beagles' lives never added up to a good investment.

"What did we get for taxpayers and pet owners here? 40 years and a grand total of zero cures at the septic shock lab. What type of ROI is that? What type of return on investment is that?” says Anthony Bellotti, President and Founder of The White Coat Waste Project

According to the National Library of Medicine, thousands of preclinical trials performed over more than five decades have discovered a handful of drugs and techniques that significantly improve outcomes of clinical sepsis.

The NIH and the Navy join a growing list that includes the USDA and the Department of Veterans Affairs, which are no longer doing experiments on cats or dogs at research facilities.

7News reached out to multiple organizations, including the National Association for Biomedical Research, American Veterinary Medical Association,Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science.

All support the humane use of animals in biomedical research.

7News asked all the questions: Are there still things we need to know for which only living creatures can effectively provide test results?

None of the four responded.

SEE ALSO | USDA no longer experimenting on kittens after 7 On Your Side gets action

After the story aired on WJLA TV, the Americans for Medical Progress reached to 7 News. We provided AMP with some of the same questions we asked other organizations that support animal research. AMP responded with the following answers:

Why did NIH use beagles for experiments? What were they studying?

Beagles, like other animal models, are sometimes used in research because of their size, temperament, and biological similarities to humans. This intramural lab at NIH was studying cardiovascular dysfunction during sepsis—a life-threatening condition that causes ~1.7 million hospitalizations per year. Heart dysfunction in sepsis patients is a very serious complication that increases mortality rates from 20% in those without cardiac dysfunction to 70-90% in those who do have cardiac problems.

Did it ever produce valuable/lifesaving results?

It's important to remember that basic science research is essential because it uncovers foundational mechanisms of how a disease affects the body or how certain processes work in the body. We need this research to pave the way for clinical breakthroughs, but sometimes this can take many years.

In this case, NIH's research deepens our understanding of what is going on with a patient's heart and circulatory system when the body is experience what's called "septic shock," something that happens when an infection threatens the entire body and can cause low blood pressure and organs (like the heart) no longer functioning correctly. A lot of times, to help bring levels back to normal, epinephrine is used to help restore blood pressure and improve circulation, especially if their hearts are struggling to get enough blood. But to this day, we still don't have a good understanding of what the best way to treat someone with these symptoms. Sometimes it's epinephrine, sometimes it's norepinephrine, or another type of vasopressor.

So what this study shows is that we need to be careful when using epinephrine in patients with cardiac dysfunction because it can cause harmful, long-lasting stress in other areas of the body, particularly at the tissue level, even after an infusion is given.

Studies like this and retrospective studies in children that were published just a couple of months ago looking at whether epinephrine vs. epinephrine is better for treating pediatric septic shock helps guide clinicians on how to not only potentially save their life but also improve the quality of their life long after discharge, to ensure they don't have health problems later.

Ending animal experiments now that we can create such sophisticated modeling with AI seems cruel and unnecessary. But is it? Are there still things we need to know for which only living creatures, even cute ones, can effectively provide test results?

Emerging technologies like AI and organ-on-a-chip systems are incredibly exciting, and AMP is a strong advocate for advancing them. But at this stage, they don’t replace the complexity of a whole living organism. For example, the way a drug behaves in the bloodstream, interacts with different organs, or triggers an immune response can’t yet be fully replicated in a dish or on a computer. At least not yet--we still need a full-body system to understand how things are working and make sure these therapies and drugs are safe. It’s not about choosing one model over the other — it’s about using the right tool for the right question. An integrative, complementary approach is how we ensure research is both ethical and effective.

Is AMP a supporter of micro-organ chips as an alternative to animal experiments?

Absolutely. AMP supports innovation across the board — from microphysiological systems to advanced computer modeling — when they help us better understand diseases or predict how a treatment might work. But these models are best used alongside animal studies, not in isolation. Until alternative technologies can consistently answer the full range of biological questions, animal research remains a vital part of scientific progress.

What does AMP think about the recent successful work of citizens, federal lawmakers and organizations that have halted animal research at USDA, NIH and Dept of Veterans Affairs?

Public engagement and accountability are critical in science, and we respect the role of lawmakers and advocates. However, we are concerned that some of these decisions are being made based on optics or pressure campaigns rather than on what’s truly needed to responsibly advance medical knowledge. Scientific progress doesn’t happen in a vacuum. If we prematurely cut off certain types of research without having equally robust alternatives ready, we risk slowing down the development of lifesaving treatments. The goal should be to improve the system — not dismantle it.